Testing Pt.3: Mind Block

Linked Insights:

The bigger the disturbance to homeostasis induced by high-intensity work, the bigger the signalling response that drives adaptation.

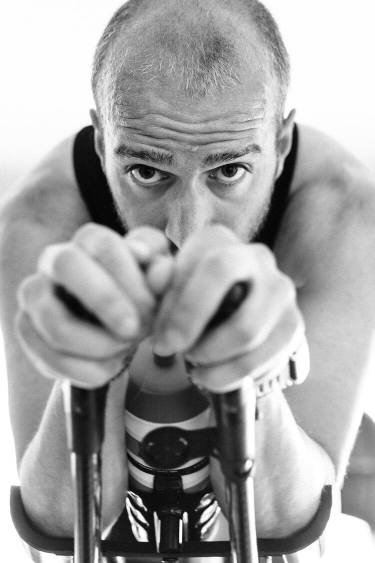

While our training structure, through careful planning of intensity distribution, reduces unnecessary stress and load, we recognise the need for hard sessions to be hard.

Really hard.

So, how hard are your tough sessions, actually? Do you feel confident walking into them? Or do you approach each one with a level of caution and fear?

With testing complete and results analysed, it was time to plan the training programme. The target was to improve my aerobic capacity, closing the gap between my CP & PVO2max.

To achieve this, intervals would need to be longer, recoveries shorter and there would need to be a strict focus on clearing out the anaerobic capacity (known as W’) early on, forcing the aerobic system to function at higher intensities. We structured just four sessions and planned to simply repeat them over a 10-12-week period with a slight adaption as I (hopefully) adjusted to the workload. Maybe it sounds boring, repeating 2 of 4 workouts each week for 12 weeks, but sometimes simplicity is essential. And, actually, these sessions were so daunting I had little confidence I’d be able to complete them until the second or third round.

The sessions themselves sound simple on paper, but the science behind them is not. By understanding an athletes W’ (pronounced W Prime | anaerobic capacity – measured in joules), sessions are planned to complete just before failure. Or not.

Let’s look at the numbers to demonstrate precision.

A workout consisting of 5x4 minutes at 350w (110%), with 4 min recovery at 180w (56%), should be possible for me. But 5x4 minutes at 355w (112%) would likely result in failure to complete the workout.

Your W’ has a finite capacity, and replenishes itself with recovery, almost like a rechargeable battery. In real practice and real-life scenarios, both may be possible on certain days. Equally, both may be impossible on certain days once everyday stress and training fatigue are accounted for. You can only plan what can be planned, and this provides a basis for designing the sessions.

Our plan for the next 12 weeks was simple: repeat 2 bike sessions every week, spaced apart with enough time for recovery, with every third week being relatively easy. We decided on shorter intervals between recovery weeks in light of the current situation, being mindful not to overwork and end up too fatigued. At the same time, we’re keeping a watchful eye on a few events which have been tentatively planned to take place towards the end of the year, COVID permitting.

So, bike sessions on a Monday and Friday, a run session on a Wednesday and the rest was all easy.

Simple, right? Only one way to find out…

The 4 workouts:

4x1min at 350w (110%), 3min at 320w (102%), 3min recovery

4x8min at 310w-320w (98-102%) at 70-80rpm, 3min recovery

8x3min at 340w (108%), 2min recovery

2x5min, 3x3min, 4x2min at 340w (108%), all with 3min recovery

With everything planned, there was nothing else to do but start.

Familiarisation

There was no doubting it, I was scared to do these sessions. I wouldn’t say I’d become comfortable with training, but I certainly knew what I thought was possible and what wasn’t. This wasn’t going to demand just a physiological change. It was going to demand a change in mindset, too.

To begin with, I planned to target the lower end of all power ranges in each session. I still wasn’t confident, but the first two weeks went pretty well, and every session was completed within the original power targets. Maybe this was just a mindset problem after all.

I sat down with my coach to try and determine if we’d accurately planned the sessions. We decided the intervals were set right, but the thing that was allowing them to be completed was more than likely the recovery intensity. This is something that I rarely would have considered before, instead, I would have decided to do whatever was necessary to complete the interval. However, bearing in mind the testing analysis, this could be the reason my anaerobic capacity has grown so much, ‘leaving behind’ my CP.

Was I simply replenishing my W’ between each interval? And was I going so easy that I was completing every interval essentially rested, and so performing anaerobically?

We calculated that 180-watt recoveries (56%) would put the sessions right on the cusp of manageability.

(Note to all those reading: it’s not advised to suddenly ramp up your recovery intervals without the advice of a coach. It’s still the interval itself where adaptation is demanded, and so it’s more critical to hit these with easier recoveries than to load the recovery and only manage half the session.)

Week 3 is lighter overall with only the one session, so I’m relishing the opportunity for some recovery.

Week 4 – walls come tumbling down?

With the new recovery power determined, we went back to the first week of the plan.

Monday? Good.

I completed the session in the aero position with an additional rep thrown in for good measure. We were well and truly in business.

Wednesday: a track run session. 30 minutes of continuous fartlek, ranging from 3:00/km– 4:00/km.

Temperature? High at 28ºC.

Result? 20 minutes spent on the floor, on my back, underneath a shade provided by the kit shed. Remember when they fried an egg on a tennis court at the US Open? Something like that.

Friday consisted of 4x8 minutes at 310-320w, 70-80rpm.

Rep 1 – 317w (100%). Rep 2 – 317w (100%). Rep 3 – 300w (94%). Rep 4 – 280w (88%).

The session was nothing short of a disaster. Within the first rep I knew it just wasn’t going to happen.

It wiped me out and resulted in a pretty useless day at work. And that’s despite consuming copious amounts of coffee and food (mainly sugar-based) just to try and inspire five minutes of productivity.

Was the intensity too hard? Was it the recoveries? The low cadence? Maybe that track session in the heat finally caught up with me? Whatever it was, the session was doomed from the start.

Rep 1 was miserable and way too hard and rep 2 was all I had left, though I did hit power targets for both.

Before I even started, I knew reps 3 and 4 just weren’t going to happen. Time to climb off, perhaps? If I can’t hit the targets there’s no point in persevering, surely?

Absolutely not.

Your body doesn’t reward you with adaptation solely because you hit 318w (100%), but not if you only held 300w (94%). Training is about pushing what you can do that day and the key is to push yourself regardless of the outcome. My heart rate still rose to the same bpm as it did when I hit the power targets, so the overall stress on my body was likely the same.

Perfection in training doesn’t come from hitting powers and paces in every repetition. It comes from turning up day in, day out.

And there’s more to training than physiological adaptation. Mental resilience grows most of all on these ‘darker’ days. These experiences provide resource to draw upon when tough times are encountered within races, in those moments where you think there’s surely no way you can keep going.

To put it bluntly, these sessions are ******* hard. I had little confidence that I’d be able to just waltz through them but, let’s be honest, they wouldn’t be very good if I did. I’m damn sure failing this session has provided me with more experience and confidence in racing that it would have if I’d just breezed through.

Week 5 focused on facilitating recovery by reducing the workload between the hard sessions. This allowed me to complete the training, including the increased recovery reps, pushing some into the aero position with an eye on a fast-approaching first race of the season.

Yes, that’s right. A race.

Our local club managed to secure the first CTT registered event since lockdown, so it looks like I’ll be lining up for a 10-mile TT next week. What better way to test out some mid-block adaptations?

That captures my mid-point reflections to date. Although it’s been incredibly tough, the accuracy and precision of the planning and subsequent training is no doubt having a positive impact, both physically and psychologically.

I’ll check-in with a final account and hopefully, a few race results in another six weeks.

For now, it’s time for a beer.